Monday, December 5, 2011

Wednesday, November 30, 2011

Tuesday, November 22, 2011

Sunday, November 20, 2011

Monday, October 31, 2011

Friday, October 28, 2011

xo

Got you drinking out them white cups, sodas

All this shit sounds foreign to you , thick smoke, choking

Baby get familiar with the order

Just crack it, then pour it, then sip slow, then tip low

My eyes red but my brim low , that XO, she climbing

Straight to the top, forget why she there in the first place

No more crying, heart rate's low, put that rum down you don't wanna die tonight

I promise, when you’re finished we’ll head to where I’m living

The party won’t finish it’s a fucking celebration

For my niggas out tonight, and they high off Shakespeare lines

There's enough to pass around , you ain't gotta wait in line

And the clocks don't work you don't gotta check the time

And the blinds don't work you don't gotta check the sky

We be going all night, til light

I got a test for you

You say you want my heart

Well baby you can have it all

There's just something I need from you

Is to meet my boys

You've been going hard baby, now you rolling with some big boys baby

Got a lot you wanna show off baby, close that door before you take your fucking clothes off baby

Don't mind, all my writings on the wall

Thought I passed my peak, and I'll experience some fall

And all I wanna do is leave cause I've been zoning for a week

And I ain't left this little room, trying to concentrate to breathe

Cause this piff so potent, killing serotonin

In that two floor loft in the middle we be choking

On that all black voodoo, heavy gum chewing

Call one of your best friends

Baby if you mixing up

Cup of that XO, baby I been leaning

Back from the come down, girl I been fiending

For another round, don't you blame it on me

When you're grinding up them teeth and it's fucking hard to sleep

I got a test for you

You said you want my heart

Well baby you can have it all

There's just something I need from you

Is to meet my boys

I got a lot of boys

And we can make you right

And if you get too high

Baby come over here and ride it out, ride it out

Work that back til I tire out

Roll that weed, blow the fire out

Taste that lean when you kiss my mouth

Get so wet when I eat you out

Girlfriend screaming that I'm creeping out

If they're not down, better keep em out

Ex-man hollering, keep him out

Hard to let go , I could teach you how

Take a puff of this motherfucking weed for now

Take a shot of this cognac, ease you out

Just one night, trying to fucking leave you out

Baby, baby

Saturday, October 22, 2011

Wednesday, October 19, 2011

Wednesday, October 12, 2011

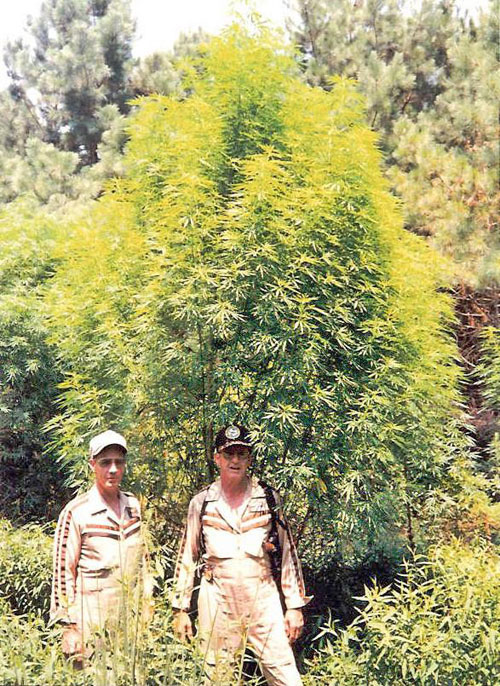

Tree Wine

Almost any fruit or plant material can be used as a base for wine making, and the marijuana plant is no exception. Marijuana wine is alcoholic, as all wines are. The basic fermentation process converts the natural and added sugars to alcohol. Marijuana wine contains about 13% alcohol when the following process is followed.

The big bonus that puts marijuana wine in a class by itself is tetrahydrocannabinol. THC, the active ingredient that gets you stoned, is soluble in alcohol. Therefore, as the wine ferments, alcohol is formed which dissolves the active THC from the marijuana. That THC then becomes part of the wine. The amount of THC in your wine depends on the amount and quality of the marijuana used in the wine-making process.

Ingredients:

1. A minimum of four ounces of stems are needed. One-half to one pound is preferred. As much leaf material as you like can be used …it makes the wine even better, but stems alone, which are usually thrown out, will make an excellent wine. DO NOT use seeds in the wine as they are very oily, contain no THC and cause a bad flavor.

2. Two fresh oranges and one lemon

3. 2½ to 3 lbs of white or turbinado sugar or 3 lbs of refined or natural sugar can be used. A mixture of honey and sugar can also be used just so it totals 3 lbs. This amount of sugars produces a wine that is just barely dry with a nice mellow flavor. If a sweeter wine is preferred, ½ lb more sugar is used; for a drier wine, ½ lb less sugar.

4. One cake of fresh active yeast (not the dry yeast)

Equipment:

1. 2 -one gallon jugs with caps

2. Several smaller bottles (Grolsh bottles work killer)

3. A 3 ft length of plastic tubing

4. Some old nylon stockings or pieces of muslin

Preparation:

1. Stuff the stems and leaves into the gallon jug. The more, the better!

2. Squeeze the juice from the oranges and lemon, strain and pour into the jug stuffed with stems. Canned or frozen juices should not be used as they contain preservatives and the wine will not ferment properly.

3. Heat 2 or 3 quarts of water to near boiling (do not use an aluminum pan). Completely dissolve the sugar or honey into the hot water

4. Pour the hot water with the sugars completely dissolved into the jug of stems. Cap the jug, shake well, loosen the cap, and set the jug aside to cool to room temperature.

5. Then, in a small amount of luke-warm water (not hot) dissolve one entire cake of yeast. It may take considerable stirring, but the yeast must be completely dissolved. Use more water if necessary.

CAUTION: Before proceeding with the next step, make sure the jug has cooled completely!

6. Pour the yeast solution into the jug, cap, shake well, and immediately remove the cap. Fill the jug to within 2 to 3 inches from the top with cool water. Be sure to leave several inches of space at the top of the jug or it will overflow when fermentation begins. Place the cap loosely on the jug.

7. Place the jug on several thicknesses of newspapers and put it in a dark place. The back of a closet is ideal. The contents of the jug will begin fermenting vigorously within a few hours. Often some of the liquid will bubble out of the jug, especially when the jug is filled too full. Just wipe it up and change the newspapers. DO NOT ADD MORE WATER!

This superactive fermentation lasts for several days. During this time it is helpful to open the jug and push the marijuana down with a clean stick or wooden spoon. Be sure to replace the cap loosely.

8. Allow fermentation to continue for 2 weeks. During this time bubbles will be rising continuously through the stems. Add small amounts of cool water during this 2 week interval to gradually fill the jug. At the same time, push the marijuana down as before. Always replace the cap loosely.

9. The total fermentation time varies, but the average time is 4 weeks. The active fermentation of the first few weeks will gradually get slower and slower until it stops. To check for completion of fermentation tip the jug slightly back and forth. If no bubbles rise up through the stems, the fermentation is complete. DO NOT SHAKE THE JUG AT THIS TIME.

Bottling and Aging:

When the fermentation is complete, carefully move the jug as not to disturb the sediment on the bottom. A sink counter is a good place to work. Insert the plastic tubing down the inside of the jug to about 1 inch from the bottom. Siphon (start by sucking on the tube) the contents into another clean glass jug. At this time it’s best to allow the wine to pass through several layers of clean nylon stocking or muslin before allowing it to enter the second jug. This will remove particles that may come through while siphoning. The wine will look murky at this time.

Discard the fermenting jug with it’s stems. It’s best to cap it, put it in a paper bag and throw the whole thing out. Take the new jug of wine, cap it loosely and put it back in the dark place. Gradually the wine will become clear and a layer of sediment will form on the bottom. DO NOT DISTURB THE JUG AT THIS TIME.

Allow it to settle and clarify in this fashion for one month then, being very careful not to disturb the sediment on the bottom, carry the jug back to the sink counter.

Rinse several fifth (or Grolsch) bottles in boiling water. Carefully siphon the wine from the jug through several layers of nylon or muslin, as before being careful not to disturb the sediment on the bottom. When the bottles are filled, cork or cap them tightly. Seal the cap or cork with electrical tape or melted wax.

The wine is now ready to drink (if you’re too eager), but it’s going to taste nasty. It’s best to put the bottles back in their dark place. The longer they are aged in this manner, the clearer, smoother and more mellow this wine will become (I highly recommend aging at least 6 months). Note: the wine will never be as crystal clear as a commercial wine, as this is a natural wine with no chemicals added.

Affects on the Body:

Marijuana wine is considerably more alcoholic than commercial wine. Drink too much and you’ll get quite drunk. The effects of the THC come on in the same manner as when you eat marijuana. You won’t feel the effects for 30 minutes to 1 hour and it will gradually grow stronger.

Marijuana Wine

Stone Age Magazine (Spring '79)

by Dr. Budrick Flint

Monday, September 19, 2011

Saturday, September 10, 2011

Thursday, September 1, 2011

Tuesday, May 31, 2011

Tuesday, May 17, 2011

Language-Based Conflict: The Ebonics Debate in the United States

One of my latest research papers.

In language and cultural studies there is a growing awareness of how language may cause conflict and the effect it has on society. In the United States, the argument concerning the status and use of Ebonics reflects this issue. For many decades, the Ebonics debate gained considerable political and cultural attention that surfaced many sensitive issues and caused tension between two communities: African Americans who use Ebonics, and the rest of society (Baron, 2000). This is partially due to the perceived notion that Standard English is the only language to foster success in the country (Bohn, 2003). The Ebonics debate in the United States is a complex and difficult subject that raises many issues on language, race, culture and education. It demonstrates how something language can cause years of conflict and disagreement. It is therefore imperative to investigate the arguments that fuel such a debate.

This paper will explore the key components of the Ebonics debate in the hope of shedding light on this language-based conflict. The focus will be on the status of Ebonics, more specifically the arguments of whether it is a separate language, a dialect, or just “bad” English. The focus will then shift toward the resolution passed by the Oakland Unified School District in respect to Ebonics in the classroom. Finally, this paper will highlight the social issues raised by Ebonics, concentrating on the perception of Ebonics, and its status compared to Standard English.

Over the past couple of decades the public discussion of Ebonics has drawn much attention to how a language should be defined (Baron, 2000). Linguists and historians alike have been contemplating whether Ebonics should be classified as a different language from English or simply a dialect of English (Rickford, 1997). Ebonics was first recognized in 1975 when Professor Robert Williams coined the term “Ebonics” to refer to the language spoken by many African Americans in the United States (Baron, 2000). Unlike other varieties of English whose status is characterized by geography, Ebonics emerged as a commonality of speech spoken by a particular cultural group (Seymour, Abdulkarim & Johnson, 1999). In other words, a form of Ebonics exists among the demographic population of African Americans (Hollie, 2001).Currently there remains no clear resolution as to whether Ebonics is a separate language or dialect of English.

Considering Ebonics as a separate independent language has been proved to be a highly controversial matter (Baron, 2000). There are many different perspectives that cover a broad spectrum of beliefs (Hollie, 2001). One theory postulates that Ebonics is a genetically based language, with a communication system that is related to the family of languages native to West Africa (Kubota & Lin, 2006). This is known as the ethnolinguistic theory, or the afrocologist view (Hollie, 2001).

Another perspective comes from the creolists, who believe Ebonics is a pidgin language that developed during the slave trade (Hollie, 2001). When African Americans were brought to the United States as slaves, from different tribes, they were not able to communicate with each other. Creolists believed this was when Ebonics was initially formed (Baldwin, 1985). The African American slaves needed a language to communicate with each other, a language the white man could not understand (Bohn, 2003). It was under these conditions that Ebonics was created, from a hybrid of other languages, which soon formed into a distinct language of its own.

Both of these perspectives credit the West African languages’ structure, with an English vocabulary overlaying that structure (Hollie, 2001). For example, they claim that Ebonics uses different non-verbal sounds, cues, and gestures, and different phonetic, phonology, morphology and syntactical rules, which English does not follow (Smith-Charles & Drew, 1998). Therefore, due to these language differences Ebonics should be acknowledged as a rule-governed and legitimate variety of English, and should be celebrated as the official, first language of AfricaAmericans (Seymour, Abdulkarim & Johnson, 1999).

While some believed Ebonics to be a separate language from English, linguists argued that Ebonics was a dialect of English (Baron, 2000). This view also made sense to the public, since non-Ebonics speakers could usually understand Ebonics without much difficulty (Billings, 2005). Furthermore, one does not have to be of African descent to use Ebonics (Myhill, 2004). Supporters of this view claim that you cannot label Ebonics as the official, first language of African Americans because there are several non-blacks who use it. Associating Ebonics with skin colour only reflects cultural separatism and standardizes a pattern of speech (Baron, 2000).

Another opinion of the status of Ebonics is that Ebonics is nothing more than “bad” English. Critics argue that Ebonics should never be given the status of a language or dialect because it is nothing more than “slang” (Matthews, 2005). They believe that Ebonics is mutant, lazy, defective, and ungrammatical “broken English” (Hollie, 2001). This was the opinion of many intellectuals and leaders who felt that elevating Ebonics to the status of a language or dialect is pure ignorance towards the English language (Matthews, 2005). For example, the Reverend Jesse Jackson once stated that Ebonics is “garbage language borderlining on disgrace” (Seymour, Abdulkarim & Johnson, 1999). It is evident that all sides of the Ebonics debate are represented by a considerable amount of empirical evidence and strong opinions. Perhaps the distinction between “language” and “dialect” is made more on social and political grounds than on linguistics ones (Wolfram, 1998).

The Ebonics debate in the United States reflects many different interests, attitudes and opinions about language (Hoffman & Butts, 1973). On December 18, 1996 the Board of Education of the Oakland Unified School District passed a resolution to facilitate African American student’s’ acquisition of the English language in the classroom through Ebonics (Seymour, Abdulkarim & Johnson, 1999). In doing so, the resolution attracted considerable media attention and sparked nationwide public controversy (Ronkin & Karn, 1999). The debate encompassed many issues, such as whether Ebonics is a dialect of English, a separate language, or simply ignorance towards the English language (Matthews, 2005). For many Americans, the passing of the resolution was seen as a way of lowering academic standards for African

Before 1996, it was assumed that Ebonics was just “bad” English. It was believed that the educational system should only teach, and allow, Standard English in the classroom (Seymour, Abdulkarim & Johnson, 1999). However, the Oakland school board had acknowledged Ebonics as a separate language and stated that it should be respected and valued in the classroom as the student’s home language (Hollie, 2001). They strongly felt that if Ebonics were to be used in a classroom setting, along side Standard English, it would actually improve African American students’ academic performance (Kubota & Lin, 2006).

With the introduction of Ebonics into the classroom, teachers were forced to adopt new pedagogy (Seymour, Abdulkarim & Johnson, 1999). Now, instead of “correcting” the child’s speech from Ebonics to Standard English, teachers used “translation” (Baron, 2000). Teachers were trained to help the students identify and translate between two separate language systems, spoken and written (Bohn, 2003). For example, when an African American student communicated using Ebonics, the teacher would accept their use of the language without directly correcting their speech. Instead, the teacher would rephrase the student’s statement into Standard English, or ask the student to “translate” the statement from Ebonics to Standard English

Although this method of assessment seemed like a simple solution critics opposed to the Oakland resolution were very verbal and open with their difference of opinion. Many believed this movement was yet another costly and wasteful educational “boondoggle” to government educational programs, and were “not supportive of a ‘loony’ idea” (Billings, 2005). Furthermore, it was not just political figures that felt that way.

After the Oakland resolution the use of Ebonics in the educational system was the butt end of television and print media humor (Baron, 2000). It was the punch line to cruel jokes and parodies that appeared endlessly on television, in magazines, the daily newspaper, and political cartoons (Wolfam, 1998). Some parodies even went as far as using racism, and displayed a clear arrogance towards this new “language” (Ronkin & Karn, 1999).

Producers of Ebonics criticism displayed negative attitudes common in speech stereotypes, and aimed to create an anti-Ebonics attitude (Seymour, Abdulkarim & Johnson,

So why was there such an objection to the Oakland resolution? One would think that focusing on language diversity in the classroom would be a high priority. It seems as though there was a need for informing members of the community about language diversity and its role in education, as well as the student’s public life (Wolfam, 1998). For example, the language one speaks is one of the most crucial keys to identity. Not only does it reflect individual identity, but one that connects with a larger, communal identity (Baldwin, 1985).

Language is also a reflection of one’s culture, and can give someone a sense of belonging (Ogbu, 1999). For school-aged children, fitting in and feeling accepted is of utmost importance. Therefore, when a child’s home language is devalued, especially from someone in a position of authority, like a teacher, it can have serious negative consequences. For example, when an African American student is constantly told, “you can’t speak that way”, or “don’t use that language”, the criticism is likely to hinder a child’s self-concept (Haskins & Butts, 1973). Clearly, the use of Ebonics as a strategy to teach Standard English was an immensely complicated educational subject (Seymour, Abdulkarim & Johnson, 1999).

Along with the educational issues Ebonics raised, it also surfaced many social concerns. Linguicism, or discrimination based on language, is a social practice that establishes power relations between members of different racial and class groups (Kubota & Lin, 2006). Language discrimination against speakers of Ebonics has been a societal dilemma for many decades. Numerous studies have shown that speakers of Ebonics are rated as less credible, and uneducated compared to speakers of Standard English (Billings, 2005).

Since the beginning of the Ebonics debate in 1995, many scholars have examined the perception of Ebonics and the relationship between dialect and credibility (Billings, 2005). In one research study, Atkins (1993) tested the factors that affect credibility in a job interview. Using a sample of 65 employment recruiters, Atkins (1993) found that speakers of Ebonics, the nonstandard dialect, were deemed incompetent.

Similar results were found in a different study that investigated the perception of Ebonics (Billings, 2005). In this study, researchers analyzed two independent variables: the race of a speaker, and the dialect of a speaker. In the first task, participants watched three different video clips: white people speaking Standard English, black people speaking Standard English, and the same black people speaking Ebonics. After each video clip was viewed, the participants completed 20 rating scales, which included scales of competence, trustworthiness, and social distance.

The results were not surprising. First, Ebonics significantly lowered the ratings of the speakers. Second, scales measuring competence were all found to have higher ratings for white speakers, no matter the dialect. Third, black speakers rated black speakers of Standard English much more highly than white speakers of Standard English. Based on these results, Billings (2005) concluded that dialect and race significantly affect the perception of a speaker. No matter what the condition, speakers of Ebonics were always found to be less credible than speakers of Standard English.

Other studies have found that speakers of Ebonics are perceived as less educated. This is partially due to the perception that Standard English is the language of the educated, and everything else is just “slang” (Matthews, 2005). But why is the standard form considered “better” than other varieties of English? It seems as though Standard English exists because it is a way to distinguish what is deemed socially acceptable and what is not (Lippi-Green, 1997). Therefore, speakers of Ebonics are subject to certain prejudices because they are not proficient in the “standard form” (Billings, 2005).

It is clear that as long as Standard English is perceived as the most prestigious form of language, the social taboo surrounding Ebonics will not dissipate anytime soon (Matthews, 2005). If these negative attitudes and stereotypes toward Ebonics are to change in the future, linguists need to take an active position and change attitudes through education and communication with the public (Sclafani, 2008).

In conclusion, the Ebonics debate in the United States is a complex and difficult issue that encompasses many issues about language, race, culture and education. It is an example of how language can cause years of disagreement and is reflective of language-based conflict between two communities: African Americans who speak Ebonics, and the rest of society.

Considering Ebonics as a separate independent language, or as a dialect of English, proved to be highly controversial. Those in favour of Ebonics as a separate independent language believed that the variety of Ebonics spoken in the United States was rooted in African American history and represented linguistic-cultural traditions (Smitherman, 1998). They believed that the linguistic and paralinguistic features of Ebonics represented communicated competence of West African slave descendents of African origin (Hollie, 2001). Because of these different features, Ebonics should be acknowledged as a rule-governed and legitimate

variety of English (Seymour, Abdulkarim & Johnson, 1999).

While some considered Ebonics as an independent language, linguists agued that Ebonics was a dialect of English because it shared many words and features with other varieties of English (Rickford, 1997). Furthermore, its speakers could easily communicate with speakers of other English dialects, and one does not have to be of African descent to use it (Myhill, 2004).

The resolution to acknowledge the existence of Ebonics as a strategy to teach Standard

The Ebonics debate also surfaced many social concerns regarding the negative perception of speakers of Ebonics. It illustrated that language discrimination can be used to establish power between racial and social groups (Kubota & Lin, 2006). This is due to the perceived notion that Standard English is more prestigious, and everything else is “bad English” (Matthews, 2005). It was evident that language is more of a political instrument that is used to gain power and status over minorities (Baldwin, 1985). Perhaps the real argument of the Ebonics debate is not about whether Ebonics should be considered a language, but rather the tension that surfaced between different communities in the United States (Baron, 2000).

References

Atkins, C. P. (1993) Do employment recruiters discriminate on the basis of nonstandard

dialect? Journal of Employment Counseling, 30, 108-118.

Baldwin, J. (1985). If Black English isn’t a language, then tell me, what is? In The price of

the ticket: Collected nonfiction 1948-1985 (649-652). New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Baron, D. (2000). Ebonics and the politics of English. World Englishes, 19, 5-19.

Billings, A. C. (2005). Beyond the Ebonics debate: Attitudes about Black and Standard

American English. Journal of Black Studies, 36, 68-81.

Bohn, A. P. (2003). Familiar voices: Using Ebonics communication techniques in the

primary classroom. Urban Education, 38, 688-707.

Haskins, J., & Butts, H. F. (1973). The psychology of Black language. New York: Barnes &

Noble.

Hoffman, M. J. (1998). Ebonics: The third incarnation of a thirty-three year old controversy

about Black English in the United States. Links and Letters, 5, 75-87.

Hollie, S. (2001). Acknowledging the language of African American students: Instructional

strategies. The English Journal, 54-59.

Kubota, R., & Lin, A. (2006). On race, language, power and identity: Understanding the

intricacies through multicultural communication, language policies, and the Ebonics

debate. TESOL Quarterly, 40, 641-649.

Lippi-Green, R. (1997). English with an accent: Language, ideology, and discrimination in

the United States. London: Routledge.

Matthews, A. (2005). The Ebonics debate in America: Will classroom use of African

American Vernacular English improve the education of Black youth in America?

Unpublished manuscript.

Myhill, J. (2004). Why has Black English not be standardized? A cross-cultural dialogue on

prescriptivism. Language Sciences, 26, 27-56.

Ogbu, J. U. (1999). Beyond language: Ebonics, proper English, and identity in a Black-

American speech community. American Education Research Journal, 36, 147-184.

Rickford, J. R. (1997, December). Suite for ebony and phonics. Discover Magazine, 18 (2).

Ronkin, M., & Karn, H. E. (1999). Mock Ebonics: Linguistic racism in parodies of Ebonics

on the Internet. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 3, 360-380.

Sclafani, J. (2008). The intertextual origins of public opinions: Constructing Ebonics in the New

York Times. Discourse and Society, 19, 507-527.

Seymour, H. N., Abdulkarim, L., & Johnson, V. (1999). The Ebonics controversy: An

educational and clinical dilemma. Topics in Language Disorders, 19, 66-77.

Smith-Charles, E., & Drew, R. (1998). Ebonics is not Black English. The Western Journal of

Black Studies, 22, 109-117.

Smitherman, G. (1998). Black English/Ebonics: What is be like? In T. Perry (Ed.) The real

Ebonics debate: Power, language, and the education of African-American children (29-

47). Boston: Beacon Press.

Wolfram, W. (1998). Language ideology and dialect: Understanding the Oakland Ebonics

controversy. Journal of English Linguistics, 26, 108-121.